Collating Until it All Makes Sense

The season of revision, learning from Texas armadillos, and many new books to celebrate.

Outside my window the trees are full of golden and scarlet leaves, which means it’s that time of year: the season of revision. I’m working with two students who have thesis manuscripts due in December, and as their advisor I have to play both good cop and bad cop. I dumped a load of manuscript comments on the two of them a few weeks ago (bad cop?) and now I’m holding their hands over Zoom as they try to figure out a way to mull my comments and alter what they care to in their books. After the comment dumping they both seemed a touch unsure if they were up to the task, but now two weeks later, they’ve made plans and they’re charging uphill toward their deadlines with something like confidence. I know exactly how they feel because I am revising too.

I lie beached for awhile after I’ve been drenched with a fresh bucket of editorial comments, however helpful they are. Eventually I struggle up and start revising. But first I have to sort through the notes from my early readers, and match them to the places they apply in my book-to-be. To do that, I take inspiration from my very first job as a human collator for a business called Pension Publications.

Travel with me back to the 1980s. If you need copies, you’re probably hand cranking them out on a mimeograph machine. For most printing needs, if you’re lucky, you have a dot matrix Epson at home that prints from a paper scroll with punched holes on the side that you need to subsequently detach. For anything professional, you need a print shop. Most copy machines won’t put the papers in order—you need to do it yourself. Here’s a clip from the 1984 film “Teachers” that shows educators squabbling over whose turn it is to use the mimeograph machine:

My mom worked for Pension Publications, which was a division of a law firm that offered pension plan templates and provided regular updates to changes in laws regarding pension plans. They had roughly a thousand subscribers who were mostly financial institutions and insurance companies.

Once a month, the Pension Publications crew printed a load of all the pages to update the pension plan, and collated it by hand, using a metal collating rack and rubber finger cots. When I was about seven, my brother and I were hired to help collate after school and we’d earn something like two bucks an hour. We worked in a big room in a strip mall, full of paper covering an array of office tables. I remember the potent smell of paper, ink, and the weird goo used to coat fingers for a better grip on the papers.

When we started, putting all those pages full of boring legal information in order looked like an unmanageable task. But we worked at it steadily and every month we somehow finished in time to make the last pickup at the post office.

What does this have to do with revision? I think when you’re faced with a huge task of processing comments and figuring out where they apply, you might need to print everything out and shuffle it around on the floor until it begins to make sense. Some people might prefer to do this digitally, but sometimes I think the task requires actual scissors and tape, and maybe even finger cots. Cut out the stuff your friend said about chapter two and pair it up with the comments your teacher and your workshop classmates gave you about the same section. Collate it all together, and see if you can discern any points of overlap. Toss out whatever doesn’t feel true to you. Then put the feedback in order according to your book’s structure, perhaps inside an outline. Voila: out of a confusing mess, you have created some sort of reasonable, chronological blueprint for yourself.

It’s daunting every time you have to do it. But then, my seven-year-old self was able to manage something like this task every month. So we can do it, right? Just watch out for paper cuts.

The Assorted Whimsy Portion of The Tumbleweed

My son’s middle school French teacher is from Texas. Because of this I’ve learned how to pronounce French words with a Texas twang, and also about the wealth of available Texas-specific French language instruction material, including the Alamo of être.

French has a past verb tense, the passé composé, which is formed by combining the conjugation of être (to be) or the conjugation of avoir (to have) with a past participle. The tricky part for non-native French speakers is figuring out which verbs go with être and which with avoir. Usually, American students are taught the mnemonic “Dr. and Mrs. Vandertramp,” to memorize the être verbs.

But if you’re from Texas, instead you get to learn the Alamo of être. This lesson comes from Tex’s French Grammar, an armadillo-based learning tool developed for students at the University of Texas at Austin. According to the authors, it follows the “epic love story of Tex and Tammy, two star-struck armadillos, and Bette, the sex kitten bent on destroying their love.”

Conveniently, all the verbs that take être in the passé composé can be illustrated by armadillos fighting to defend the Alamo—arriving, leaving, returning, dying, and falling. I was going through the verbs with my son and he said, "I still don't understand—what is the Alamo?"

I told him he’s from Colorado and he doesn’t need to know.

The Book Recommending Portion of The Tumbleweed

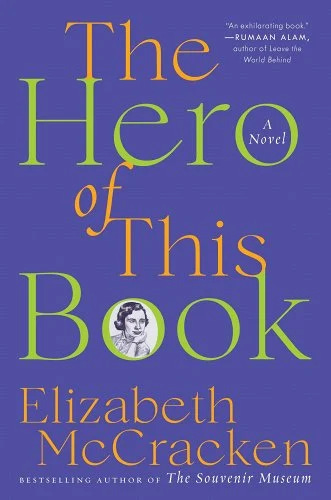

I want to recommend Elizabeth McCracken’s hilarious and heartfelt new novel, The Hero of This Book, which blends elements of memoir and fiction in recounting a trip the narrator took to London the year after her mother died.

I reviewed for the Minneapolis Star Tribune:

“The narrator has an endearing way of insisting she knows nothing and then dropping one stellar insight after another. As she walks around London and thinks about the estate sale that emptied her parents' jam-packed house, and the prospective buyers who are trooping through it now, she accuses this book of having ‘not much of a plot.’

But it actually follows a plot that the bereaved know well. Researchers have documented how grieving people often engage in searching behavior as their brains struggle to integrate loss. A mourning brain seems to ask: Where did my person go? Memories play in loops, and people can even hallucinate seeing their loved one. This doesn't happen to the narrator, but her mother appears as an overlay to every experience. She walks around seeking and feeling, and observes about writing, "Unlike some pursuits, if you hurt yourself, it's a sign that you're doing it right."

This compact, wise, heartfelt book is another sign that McCracken continues to do it right.”

The Self-Promotional Portion of The Tumbleweed

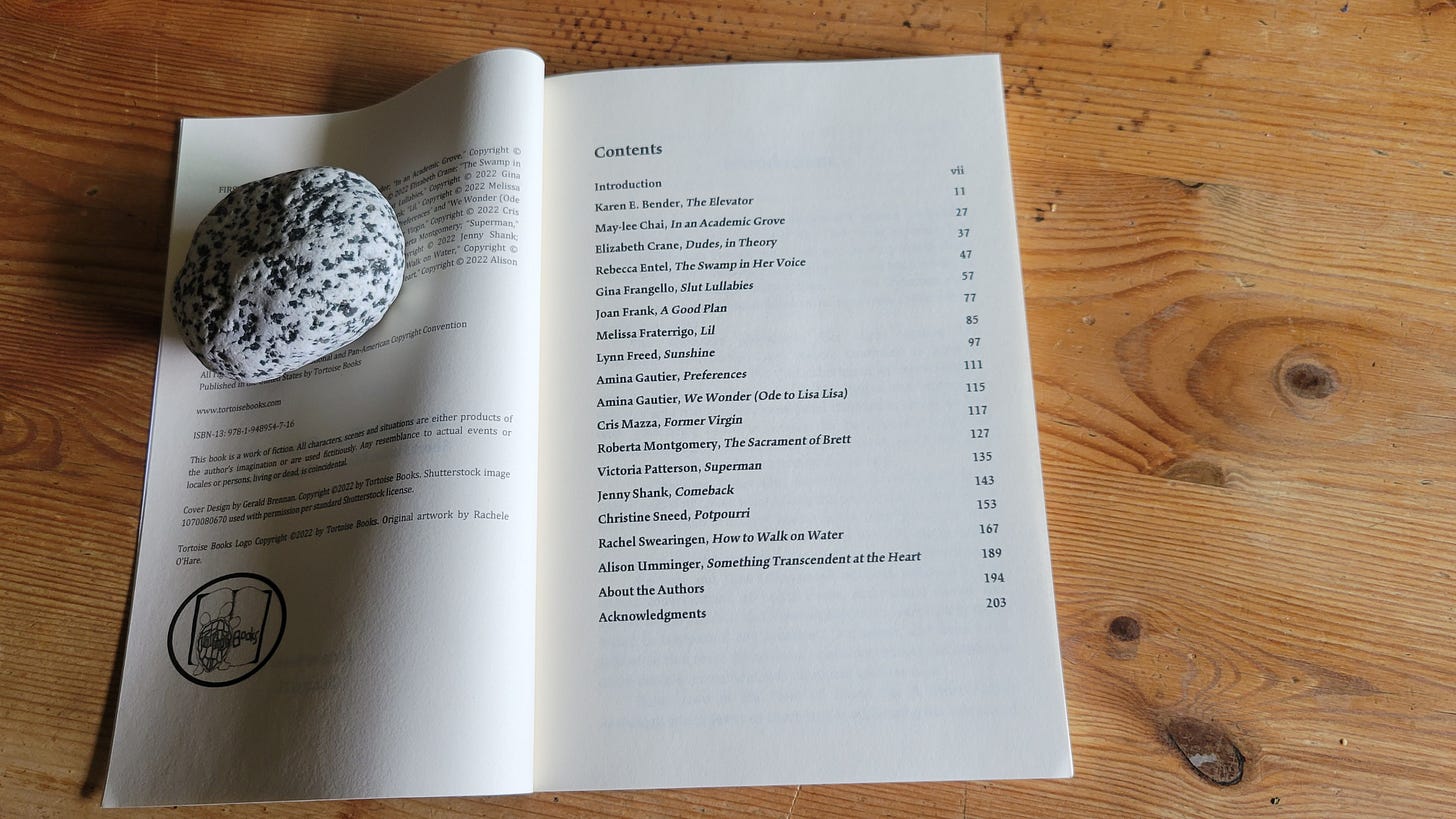

The fiction anthology Love In The Time of Time's Up, edited by Christine Sneed, is out now! It has a story of mine alongside stories by a slew of amazing writers. Christine’s new novel, Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos, is out now too!

My friend Shann Ray Ferch, who is an award-winning fiction writer, poet, and professor of leadership and forgiveness studies at Gonzaga University, was kind enough to interview me about Mixed Company for Full Stop.

The Mile-High MFA program is partnering with Tattered Cover to host a quarterly reading series that celebrates the work of our faculty, students, and alumni, and for the first one, I will read with my colleague Traci L. Jones and my former student, now twice-published author Hillary Leftwich. We’ll read at the Westminster Tattered Cover on November 1 at 6 p.m.

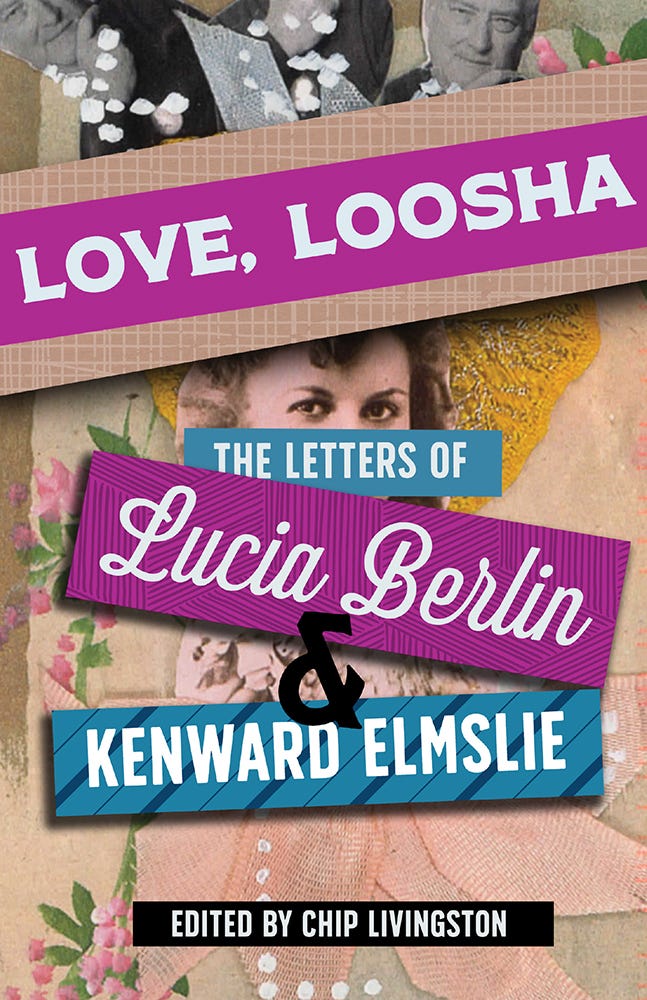

My friend Chip Livingston has edited a volume of letters between our teacher Lucia Berlin and her dear friend, accomplished opera librettist and poet Kenward Elmslie. The Lighthouse Writers Workshop will help us celebrate the release of Love, Loosha by the University of New Mexico Press with a Zoom event on December 14. Stay tuned for more details.