Discerning Your Calling: Richard Wright and the Price of Eggs

How should a person be, a Denver Nuggets Valentine, a fantastic graphic novel, and February events.

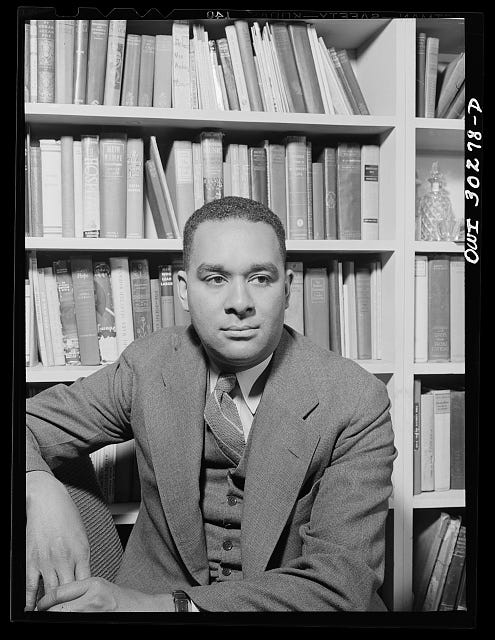

Richard Wright published his classic memoir Black Boy in 1945 following the success of his collection of novellas, Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), and his best-known novel, Native Son (1940). In 1944, Wright submitted the finished manuscript to his publisher, who accepted it and scheduled it for publication.

However, Book of the Month Club, who’d previously selected Native Son as its first featured title by a Black author, told Wright and his publisher they only wanted to print the first part, called “Southern Night,” that covered his childhood in the South up to age 19. Book of the Month Club exerted an outsized influence on American literary culture in the 1940s, as its reach had expanded from 363,000 members in 1939 to 889,000 subscribers by 1946. Wright agreed to publish the first half of his memoir separately in 1945. Black Boy sold half a million copies in its first edition and through Book of the Month Club. The book has since been published in a restored edition that includes the second part, “The Horror and the Glory,” covering Wright’s young adult years in Chicago.

Both my kids read Black Boy in their tenth grade English classes and enjoyed it so much they didn’t understand why they were only assigned to read part one. Part one detailed Wright’s harrowing childhood. He grew up in poverty in the Jim Crow South, starving as his ailing single mother moved from place to place to try to keep him and his brother alive. Wright didn’t complete an entire year of school until he was twelve. He faced beatings and racism, lack of access to reading material, and a constant barrage of people telling him he’d never be a writer. How did he develop the towering intellect, instinct for beauty, and fathomless sensitivity that is showcased on every page of his work? My kids wanted the answer and wanted to know why their teachers didn’t have them read on. I did too. Plus I’m nosy. So I read the second half.

First of all, the teachers made the right call. I imagine their faculty meeting about this matter was brief. “So, for our unit on memoir, we don’t have the kids read the part that’s like all boring Communist meetings, right?”

Because what Wright mostly faces next as he tries to boost himself into a life of letters in Chicago is a series of tedious Communist party meetings. In 1930s Chicago, the Communists were one the only groups who offered desegregated meetings, the only group that had any interest in pursuing civil rights for Black Americans. Plus, the Communists had a really good literary magazine, and provided Wright his first opportunity for publication (outside of a voodoo genre story he’d published in a Southern newspaper during his youth). The journal New Masses didn’t give only Wright his literary break—Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker and more published early work there.

After seeing Wright struggle to gain access to library materials and time to write throughout the first section of Black Boy, you can understand why Wright cozied up to the only group of people who treated him and his work with dignity.

However, his halcyon years in the Communist party did not last, because the Communists, like all ideologues, were invested in making sure everyone thought and acted in exactly the same way, and liked to hold frequent boring meetings. Wright soon realized, as they placed restrictions on his writing projects, that you can’t make art out of propaganda.

The series-of-Communist-meetings portion of Black Boy felt familiar to me, as someone who has watched the entirety of A French Village, the seven-season French television drama that follows the citizens in a small French town during World War II’s Vichy era. One group of reliable Nazi resisters in France was the Communists. And yet, the parts depicting their meetings are the only boring portions of A French Village—there are denouncements, loyalty oaths, the reciting of Leninist tracts, people getting hot under the collar about who the better Communist is. You could cut the meetings from A French Village and stick them into Black Boy and I would not notice the difference, probably even if you left the scenes in French.

Once Richard Wright finds literary support and education in Chicago, he gets serious about reading. “I discovered that it was not wise to be seen reading books that were not endorsed by the Communist party,” he writes. And he gets serious about writing, eventually working on the book that will become Native Son. But the Communist Party has a different assignment for him.

A party leader tells Wright they want him to put aside his writing and “organize a committee against the high cost of living.” Wright does not want to do this, but rather than reject the request of his only community, he at first accepts, setting his writing aside to attend boring meetings. “I gritted my teeth as the daily value of pork chops was tabulated, longing to be at home with my writing. I felt that pork chops were a fundamental item in life, but I preferred that someone else chart their rise and fall in price.”

Eventually, Wright can’t ignore the call of his yearning to write. He refuses the Communist party’s assignments, and they part ways in mutual disgust. (He wrote about it in the essay “I Tried to be A Communist.”)

Pause on this: a Black man who has been told he’s worthless his entire life, told he’d never be a writer, refused education, refused library materials, eventually edging out of poverty as he works as a street sweeper for thirteen dollars a week, decides he will become a writer anyway.

Richard Wright didn’t have much power, but he had the power to chose where to spend his precious free time and attention. There were so many problems in America at that time—the Great Depression, Jim Crow laws, rampant racism, punishing income inequality. Wright could have decided that he should try to follow orders and solve some of those problems, specifically the grocery-price-related ones. But he believed in himself enough to discern that his most valuable contribution toward solving these problems would be his art. He let someone else worry about the price of pork chops and eggs. He had a book to write.

Today, the price of groceries is high in America again, income inequality is worse than it was before the Great Depression, lawless, racist shysters and oligarchs are trying to peel back the gains of the Civil Rights Movement and trash our democracy, and there are fires and floods everywhere. There is a lot going on. So, where will you put your attention? What are you best at? What do you have to contribute that no one else can?

Richard Wright believed in himself when he had next to no encouragement. Because of that self belief, he wrote Native Son, a book whose themes and ideas contributed to the Civil Rights Movement.

You can believe in yourself too. Who knows what impact the art you make today will have? Let someone else tabulate the price of eggs, while you spend your time focused on sharing your most exceptional gifts. Each of us honing our unique contributions as an offering toward the greater good has always been how our country has found its way out of a mess. This mess is big—I don’t know how it ends, but the effort of good people doing good work because they believe in liberty and equality is never wasted.

Happy Black History Month, Tumbleweed friends!

The Assorted Whimsy Portion of The Tumbleweed

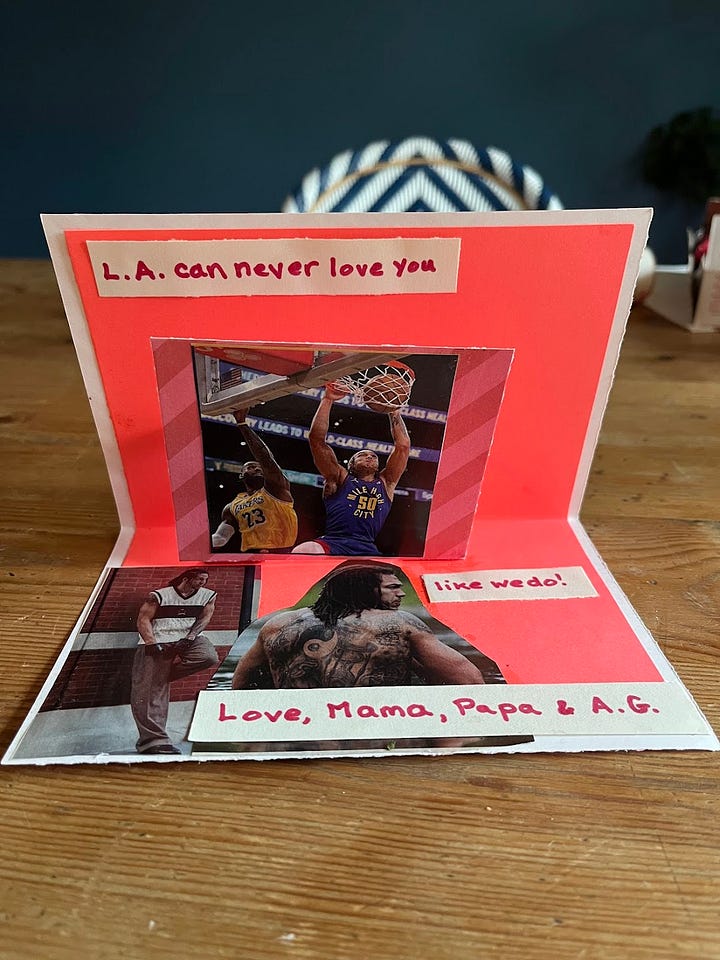

My daughter is in college near Los Angeles, but I wanted to make sure she keeps her priorities straight, so I made her a Valentine with a pop-up of Aaron Gordon of the Denver Nuggets dunking on LeBron James.

Aaron Gordon wasn’t available so I signed the card for him. I trust A.G. won’t mind.

The Book Recommendation Portion of The Tumbleweed

I just read the most extraordinary graphic memoir, Feeding Ghosts by Tessa Hulls. Hulls grew up in Northern California with her British father, her Hong Kong-raised mother, and her Chinese grandmother Sun Yi. Sun Yi had been suffering severe mental illness for years before Hulls was born, and that paired with the fact that Hulls didn’t know any of the Chinese dialects her mother and grandmother spoke, meant that she felt disconnected from both women until she set out to research, write, and illustrate this story.

As she investigates her grandmother’s past as a journalist in Shanghai fleeing Communist persecution, Hulls does not settle for easy truths. Even when she’s ascertained a fact that seems solid, that she could just run with, she continues to interrogate it, and when she finds two plausible “truths” that contradict each other, she holds them both up for the reader to examine. This book is a courageous excavation into the past, the family, and the self.

There’s a phrase to describe tenacious, gifted athletes who want something so badly that their scrappiness shows in their work that I’m going to apply to Tessa Hulls: Feeding Ghosts proves that as a writer, artist and storyteller, she’s got that dog in her.

The Happenings & Links Portion of The Tumbleweed

I am still observing my winter hibernation period, but on Saturday, February 22 I will emerge in a flurry of activity:

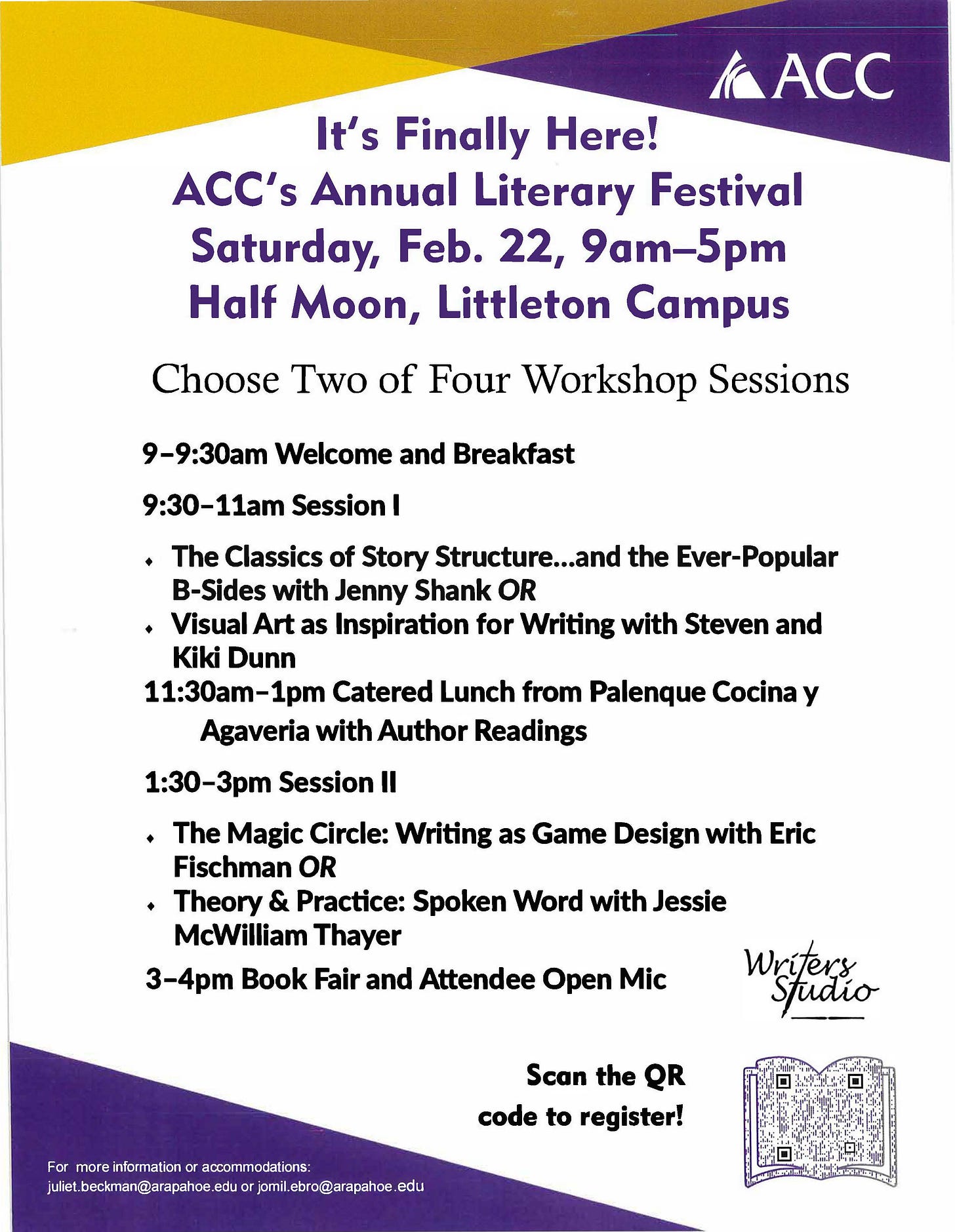

On February 22 in the morning, I will join the Arapahoe Community College Lit Fest to teach a class about classic story structures (like the quest and the stranger) and popular alternative structures (like the crazy neighbor story). Attendees can choose two from the four classes by me, Steven Dunn, Eric Fischman and Jessie McWilliam Thayer, plus enjoy lunch for just $30 for students, $50 for general admission. Register here.

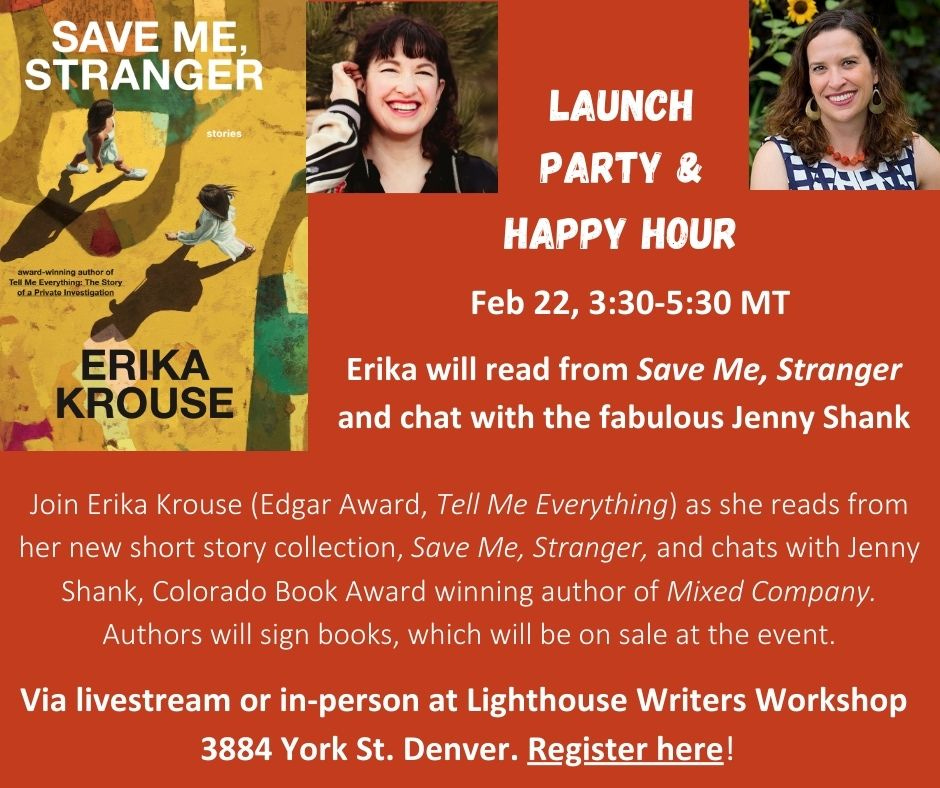

On February 22 in the afternoon, I will celebrate the book launch of one of the best writers around, Erika Krouse! Fresh off her Edgar Award win for the amazing Tell Me Everything, Erika will discuss her new collection of kickass short stories, Save Me Stranger, with yours truly. The whole shebang starts at 3:30 p.m. with a happy hour mingler, a reading and talk at 4:15, and a book signing at 5:15. Plus, it’s free for Lighthouse members, so save your pennies for the book that you are going to want to purchase and devour. (Trust me.) Save Me Stranger is in bookstores now, and one of its stories, “Eat My Moose” is a finalist for an Edgar Award and will be featured in the Best American Mystery Stories 2025, selected by John Grisham! I knew her when…

On February 22 in the night, I will hopefully be supine, watching my Nuggets play the Lakers, who have once again regenerated due to dastardly trade majicks.

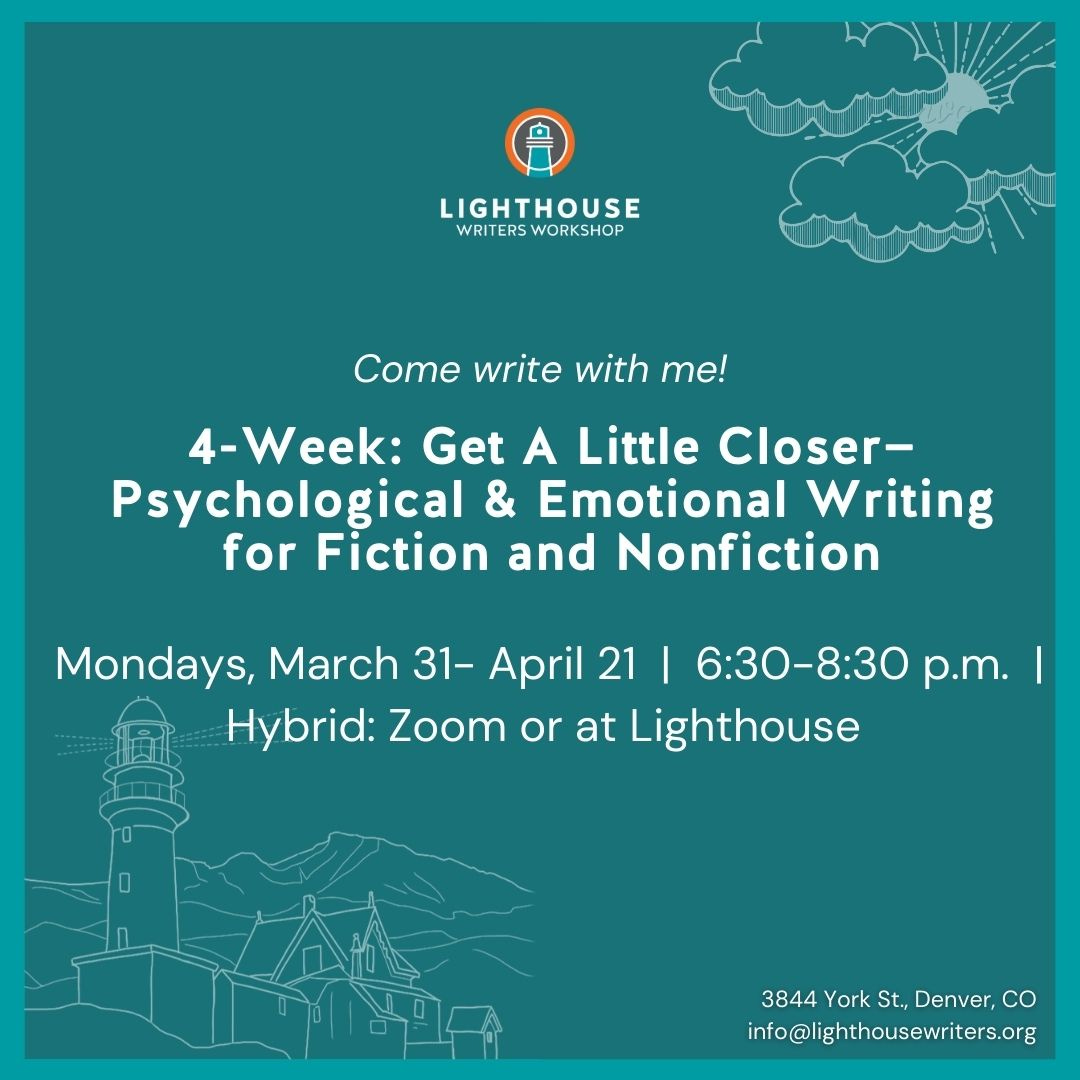

I’ll be teaching two 4-week classes for Lighthouse this spring, both hybrid, so you can join on Zoom or in person at Lighthouse HQ. First it’s Get A Little Closer: Psychological and Emotional Writing for Fiction and Nonfiction, on Mondays, March 31-April 21 (6:30-8:30 p.m.). Next, it’s Seeing the Big Picture: Techniques for Revising Fiction and Nonfiction Books, on Tuesdays, April 29-May 20 (6:30-8:30 p.m.).

Speaking of the Lakers, I’ll be heading to Los Angeles for the upcoming AWP conference in March. I will sign copies of Mixed Company at the Texas Review Press booth on Thursday, March 27 at 11 a.m. and I’ll be on a panel on Friday, March 28 called “Making the Cut: What Judging Story Collection Contests Taught Us.” Led by Flannery O’Connor Prize editor Lori Ostlund, I’ll be talking about what made certain story collections stand out to me, alongside my fellow screener judges Toni Ann Johnson, Michael Wang and Hasanthika Sirisena.

Find me on Blue Sky at @jennyshank.bsky.social!

As always, The Tumbleweed welcomes your questions and comments about writing, reading, taco eating, the Denver Nuggets, rabbit wrangling, Deion Sanders, Ralphie the Bison, and baby seals.

Notes on the Cost of Eggs. https://shorturl.at/xTn1R