Saying Goodbye to the Tumbleweed's Rabbit-in-Chief

It's okay to mourn losses of any size. That's how you know your heart still works.

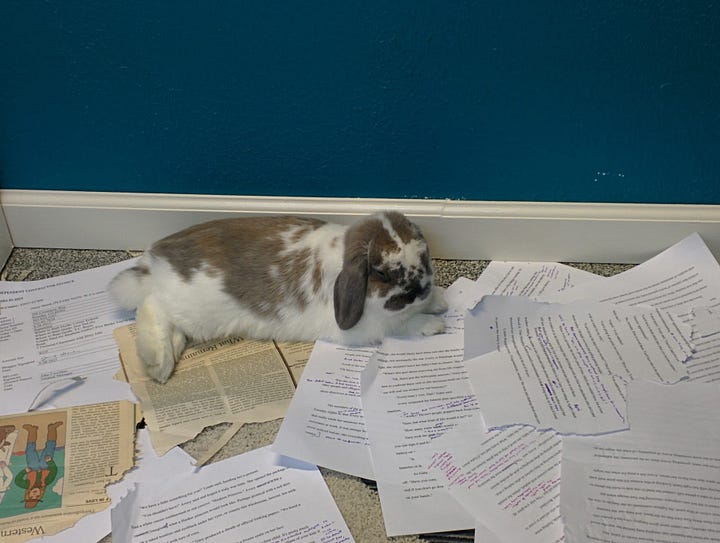

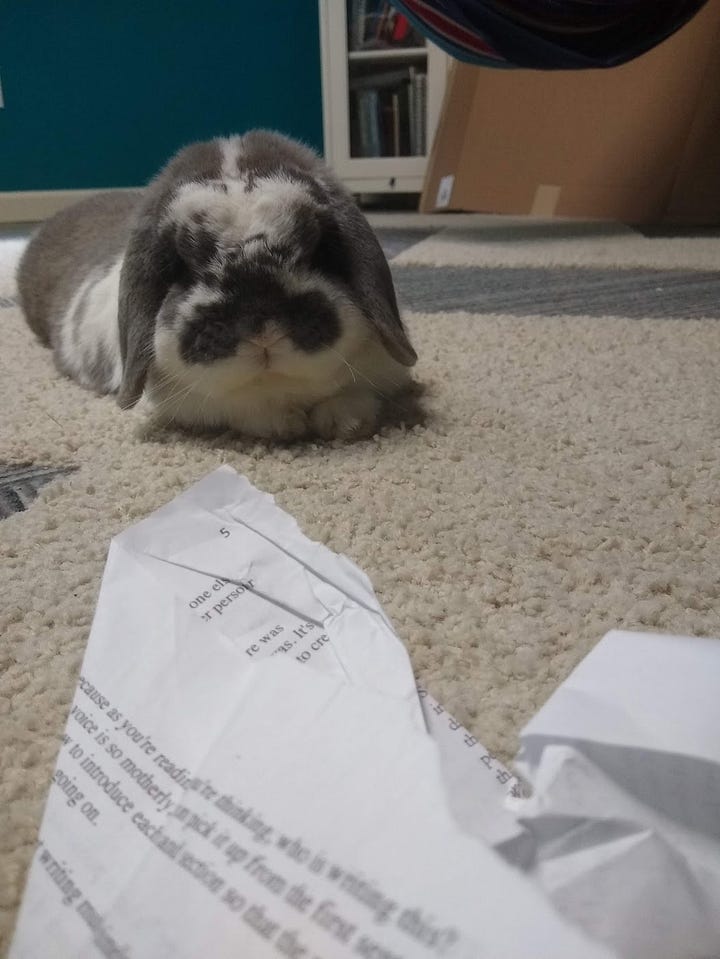

Nine years and two months ago the best rabbit in the world was born in Berthoud, Colorado, and my daughter brought him home, named him Floppy, and trained him to use a litter box. He became a steadfast friend, visiting me in my office, where he served as my editor, napping while I wrote and chewing printouts of old drafts that I'd let drift to the ground. His editorial comments assured me that everything I'd let go was best cut for good, and possibly even digested. Some weeks he edited so vigorously that I'd visit the online rabbit forums, making sure it was okay for him to chew through so much paper.

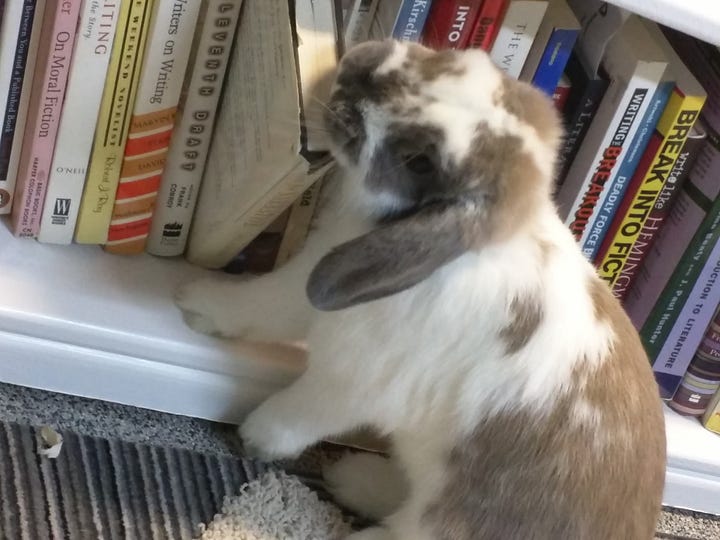

When Floppy was young he'd pull books off the bottom shelf in my office and nibble at those too. He loved head pats and cilantro and just being by everyone's side, nipping my socks when I followed along with a yoga video. You had to be careful when you walked downstairs because Floppy was so eager to greet you that he'd hop all around your feet, confusing your steps. He moved silently so often I'd be rushing through to grab something and he'd sneak up behind me and insist I slow down and give him an ear scratch. He was sweet, but also maintained his bunny boundaries, letting you know what he wanted and didn't want by thumping his foot or nudging you away with his nose.

About a year ago we noticed Floppy stumbling when he rushed out to claim his vegetables. He was always in a hurry to arrive at his lettuce—he dashed toward it with joy and ate it with abandon, no matter how many times we served him the same salad. But now his hind legs couldn't keep up with his enthusiasm, and he'd flip onto his side as he tried to scurry forward.

We checked with the veterinarian, who told us to make his area more accessible. So we made Floppy a ramp up to his litter box and put out towels when he lost his footing on the concrete floor. Then a few weeks ago, he stopped being able to move his back legs entirely. I was busy teaching at Lit Fest and I'd try to help him whenever I was home, moving his food where he could reach it, changing out his towels, and sweeping up after him when he couldn't climb into his litter box anymore. We were all cleaning him a lot but it wasn't enough—his fur was getting matted even though we used baby wipes and saline to clear his eyes like the vet suggested.

The day after I finished teaching at Lit Fest I brought Floppy to the vet, who told me what I was expecting but still didn't want to hear. Floppy's mobility problem was likely a neurological one, and wouldn’t improve. He couldn't keep himself clean anymore, which would lead to infections. And the health of a rabbit's digestive system depends on them hopping around a lot. Since he couldn't do that anymore, soon he'd get sicker and be in pain. I knew it was time to help him rest.

We come to pets with our grief and troubles, and they help us through it. We sit next to them, sad and uneasy, and they accept us, letting us pat them for as long as we need, keeping us company when we can't be alone. And then they remind us when it's time to get up, to rejoin the world of duties and struggle—shouldn't we be going on a walk? And shouldn’t you be fetching my treats now? That's why it's so hard to lose them, when they are a key part of what keeps us going.

I told my friend, the wonderful writer Paula Younger, about Floppy's decline and she urged me to do what had to be done. "I grew up on a farm," she said. "When animals are suffering, you need to euthanize them. My family calls me the Angel of Death."

I think that's a compliment. Paula has weathered a great many losses, not just of animals, but of vital people she couldn't bear to lose. She has taught me how to bear witness to the end of life. When she's had relatives with terminal illnesses, and other people turn away, she's gone toward them. She's sat by their side. She's taught me not to abandon the dying, and never to forget the people around us who are grieving.

And so I know it's my job to make Floppy's last appointment, to invite his lifelong bunny sitters over to say goodbye, to figure out what to do with his remains. The whole process is searing but I know I have to face it. Floppy is teaching me how to do all this—it's his final kindness to me. And I tell myself it's okay that I'm taking this little loss so hard. Grieving little losses along the way to big ones is how we know our hearts still work.

I have friends who lost a parent when they were scarcely more than kids and I have friends who've suffered the excoriating loss of their children. There are children in refugee camps and war zones who are hungry and grieving, and there are parents of those kids in absolute desperation, unable keep their kids safe and fed. These mourners are the lead ones, singing arias of grief that we should pay attention to and honor. But it's okay for those of us with smaller losses to mourn them in the background. We are the rhythm section and the chorus, keeping the beat, practicing for the day we hope won't come, when we will be called to take the lead.

I've been buying two bunches of cilantro, Floppy's favorite treat, every week at the grocery store for nine years. So if you ever see me weeping over a bowl of guacamole, you know why. And if you ever want to tell me about your good kitties, your best pups, your dear horses, you know I'll listen.

The Book Recommendation Portion of The Tumbleweed

I recently reviewed a beautiful memoir by Sister Marya Grathwohl, This Wheel of Rocks: An Unexpected Spiritual Journey for Jesuit Media Lab. Grathwohl has become known as a keen environmentalist for her work leading projects to help nature and indigenous people in Montana and elsewhere. I wrote:

As a child, natural beauty stirs Grathwohl into reverie. She writes about becoming overwhelmed by a field of snow-covered Queen Anne’s lace, and trying to explain it to her dad. He tells her, “Just go back out to Frey’s hillside and stand there in the middle of those snowy flowers. Stand there until you can feel them inside you, in your heart. Then you will never forget.” She follows his instructions, and realizes this was her “first lesson in contemplative prayer. It’s the same practice, whether in a mountain meadow, a hospital room, or a convent chapel. Show up, take time, feel the beauty in your heart.”

The Happenings & Links Portion of The Tumbleweed

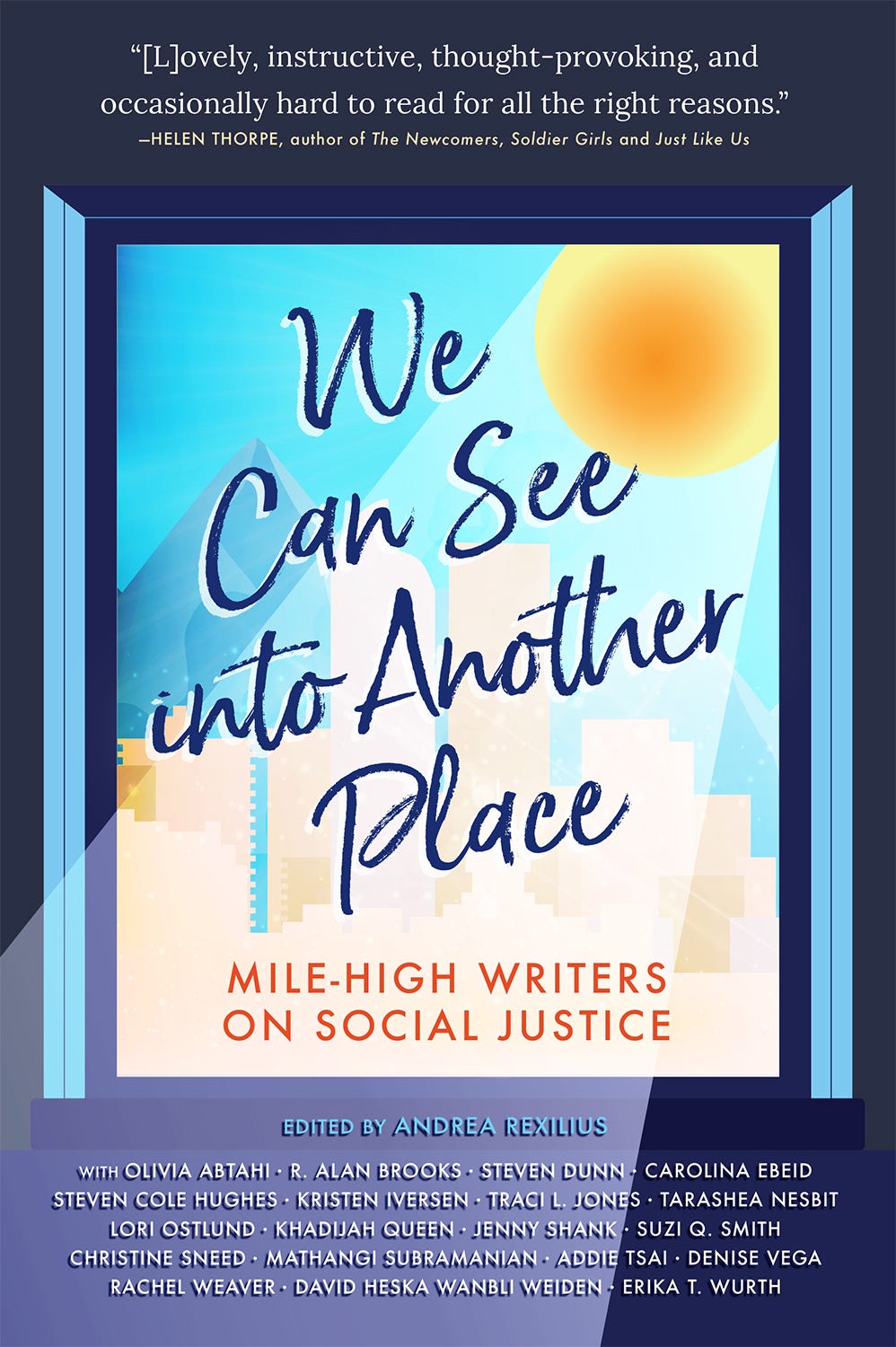

The new anthology edited by poet, teacher and MFA program director extraordinaire Andrea Rexilius, We Can See Into Another Place: Mile-High Writers on Social Justice, will be officially released on July 1! I am so proud to have an essay in it alongside beautiful work in a variety of genres by my Mile High MFA colleagues.

This September and October, I’ll be teaching an online fiction class for Jesuit Media Lab, “Writing Techniques Inspired by Catholic Fiction.” We’ll meet asynchronously on the Wet Ink platform, and also participate in a couple of Zooms. Each student will have a chance to receive story feedback from me! Watch this page for more details.

As always, The Tumbleweed welcomes your questions and comments about writing, reading, taco eating, the Denver Nuggets, rabbit wrangling, Deion Sanders, and baby seals.

Awwww. I’m sorry Jenny. Our pets are our silent friends who nonetheless make our lives so much richer. I’ve enjoyed reading about Floppy through the years and would be sad without reading this lovely rumination. I love the shout out to our dear Paula, who has never been afraid to run towards these instances.

Whenever we had to put one of our dogs down, I always thought, "We took him [or her] as far as we could." But my wife eventually corrected me – she told me that it was the dog who had taken us. As always, she was right. Thank you for the story of faithful Floppy, rabbit of note.

"All sorrows can be borne if you put them into a story or tell a story about them." (Isak Dineson)